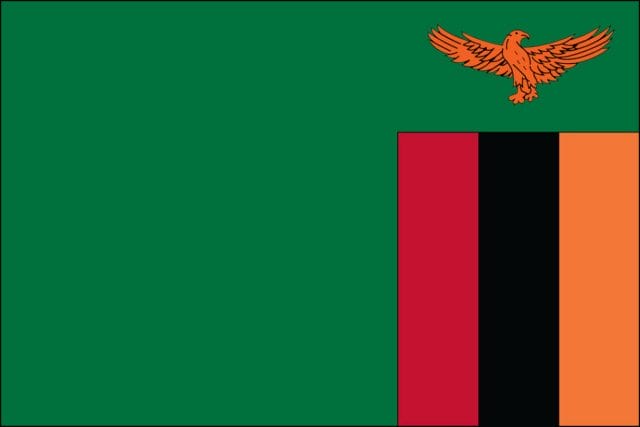

Zambia: The Privatisation of State-Owned Assets Explained

By Henry Kyambalesa

INTRODUCTION

News stories concerning the privatisation of Zambia’s State-owned enter-prises which took place 30 years ago have continued to linger in the coun-try’s news outlets. In this article, I wish to provide a non-partisan bird’s-eye view of a process that was mainly fostered and funded by our coun-try’s development partners, whose experts directly participated in the pri-vatisation process.

The development partners, whose support was cardinal to the consumma-tion of the privatisation process, included the Danish International Devel-opment Agency (DANIDA), the German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ), the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Official Development Assistance (ODA), the United Nations Develop-ment Programme (UNDP), the United States Agency for International De-velopment (USAID), and the World Bank.

As a backdrop to the discussion, I will provide a brief survey of Zambia’s changing economic scenarios since independence on October 24, 1964. Thereafter, I will briefly discuss matters relating to Zambia’s Privatisation Act No. 21, as well as tender several reasons why Zambia should consider privatising its current State enterprises.

1.1 The UNIP Era:

As Fundanga and Mwaba (1997:5) have observed, our beloved country adopted a fairly prosperous economy at independence—an economy that had a well-established private sector dominated mainly by large expatriate business entities. And, as Bigsten, Mulenga and Olsson (2010) have noted, our country was one of the richest of the newly independent developing countries in Africa at independence in 1964.

Currently, however, three out of four citizens in the country live in ex-treme poverty and, according to USAID (2020), the country faces a multi-tude of challenges, including high unemployment, low agricultural productivity, inadequate transportation and energy infrastructure, and lim-ited government capacity to plan and manage national development.

The country’s economic problems started soon after the country’s politi-cal independence from Great Britain. In April 1968, August 1969 and No-vember 1970, former presi¬dent, the late Dr. Kenneth D. Kaunda, made pol-icy pronounce¬ments in his addresses to the Nation¬al Council of the Uni¬ted National Inde¬pen¬dence Party (UNIP)—pronouncements which were aimed at nationalising privately owned enterprises.

By the end of 1969, State ownership of business entities encompassed all industrial and services sectors of the country’s economy, including agri-culture, airline and bus services, baking, hotels and tourism, milling, min-ing, real estate (partly the construction of houses), the timber industry, and utilities—including the supply of water and electricity.

Essentially, UNIP’s socialist policies barred both local and foreign private inves¬tors from medium and large-scale commer¬cial and indus¬trial sec¬tors of the countr¬y’s econo¬my from the mid-1960s to 1991. Naturally, the mo-nopolistic position enjoyed by State companies in the country’s economy culminat¬ed in com¬placence and gross inefficien¬cy because, in the absence of competi¬tion, they appar¬ently found it unneces¬sary to seek or use tech-nologi¬cal inven¬tions and innovations that would have improved the quali-ty and quantity of their outputs.

The culmination of such a state of affairs was a national economy that was characterised by rampant and unprecedented shortages of commodities, and, among other socioeconomic ills, an escalation of black markets for the commodities.

1.2 The MMD Era:

The unprecedented socioeconomic problems facing the country during the UNIP era partly prom¬p¬t¬¬ed the next govern¬ment of the late President Fred-erick T. J. Chiluba to embark on an ambitious priva¬tisa¬tion programme upon his inaugu¬ration in October 1991 in an attempt to boost competi¬tion in com¬merce and indus¬try.

In making the transition, he summed up his thinking about the role his ad-ministration was going to play in the creation of an economic system in which commercial and industrial activities were the pre¬ponderance of the pri¬vate sector in the following words: “Never shall the Government allow the selling of soap and foodstuffs to be its business” (Nyakutemba, 1992:32), and “We will pri¬vatise everything … from a toothbrush to a car assem¬bly plant” (Ham, 1992:41).

As Chilipamushi (1994:16) has noted, privatisation was expected to stimulate private investment, give econom¬ic power to a greater number of people through stock ownership, promote competition and encourage effi-ciency in commerce and industry, beef up government coffers through the sale of govern¬ment holdings in state enterprises, as well as ease the finan-cial burden of state compa¬nies on the public treasury.

And, as Pitelis and Clark (1993:7) have maintained, the reduction of gov-ern¬ment involvement in commerce and industry that would follow the pri-vatisation of State enterprises was expected to result in reduced public-sector borrowing and government spending.

Also, State-owned assets and enterprises, to paraphrase Muuka and Abu-baker (2002:16), could easily become vehicles for embezzlement and bribery for personal aggrandisement, often at the expense of the imple-mentation of aid-financed projects, and could also foster the development of cronyism through patronage at the highest levels of government.

Moreover, they could bolster the siphoning-off of public resources for party, political or factional purposes, as well as trigger the packing of pub-lic enterprises with supporters of the ruling political party without regard for genuine personnel requirements.

The following excerpts should provide some of the other worthwhile ben-e¬fits associated with privatisation: “Privatisation of state enter¬prises is an extension of democracy because it removes politi¬cal inter¬fer¬ence from the running of business¬es” (Chitalu, 1996). And “There are heavy costs asso-ci¬at¬ed with the conversion of a State-controlled economy into a free mar-ket system, such as increased unemployment; in the long run, however, the free market system holds great promise for everyone” (Mwewa, 1996:36).

1.3 The PF Era:

During the late President Michael C. Sata’s administration between 2011 and 2015, the Zambian government changed course and reverted to eco-nomic policies pursued by UNIP between 1968 and 1991 by creating the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) in 2014—a Corporation that is different from the Industrial Development Corporation (INDECO) that was established by the UNIP government in abbreviation only.

According to the Patriotic Front (PF) government, IDC is a state-owned en-terprise (SOE) charged with the mandate to spearhead the country’s com-mercial investments agenda aimed at strengthening the country’s industri-al base and job creation. It is wholly owned by the government through the Ministry of Finance.

And, like its predecessor, IDC’s operations encompass all industrial and services sectors of the country’s economy, including agriculture and for-estry, energy, financial services, healthcare, information and communica-tions technology, infrastructure, manufacturing, mining, real estate, tour-ism, and transportation and logistics.

It took almost 20 years of State ownership of major economic units through INDECO from the late 1960s to the late 1980s for the country to experience the following dour effects of extensive State ownership of economic units:

(a) Unprecedented shortages of essential commodities;

(b) Evolvement of black markets for essential commodities;

(c) Chronic loss-making operations by SOEs;

(d) A shortage of foreign exchange reserves due to failure by SOEs to generate foreign reserves through exports;

(e) Deepening government deficits partly emanating from govern-ment’s efforts to bail out loss-making SOEs; and

(f) Escalation of smuggling of essential commodities into and out of the country.

IDC has been in existence over the last 6 years. If the government cannot change course by re-privatising the SOEs under the IDC group of compa-nies, we should eventually not be surprised to witness history repeating itself sooner or later.

PRIVATISATION ACT NO. 21

In July 1992, the Zambian Parliament enacted the Privatisation Act No. 21, which promptly established the Zambia Privatisation Agency (ZPA) as the sole institution charged with the responsibility of privatising State-owned enterprises.

The Agency was to be governed by a Board of Directors to be constituted from civil society and government institutions, and was granted the auton-omy to determine how the State enterprises and assets were to be sold and the prices that were to be paid for them, while Cabinet’s role was confined to the approval of the sequence of the privatisation process.

Specifically, the purposes of the ZPA Board of Directors, according to An-glo-American (2002), were to plan, manage, implement, and control the privatisation of State-owned enterprises by selling them to individuals and institutions with the wherewithal and expertise to run them on a commer-cial basis.

With respect to the overall divestiture or privatisation programme, the fol-lowing is a summary of the companies privatised by October 31, 1996 cit-ed by Fundanga and Mwaba (1997:11) and sourced from a press release by ZPA (1996):

(a) 18 companies were sold to Zambian individuals through competi-tive bidding;

(b) 41 companies were sold to Zambian companies through competi-tive bidding;

(c) 13 companies were handed back to previous Zambian owners;

(d) 16 companies were sold to Management buy-out teams;

(e) 5 companies were sold to foreigners with Zambian minority partici-pation;

(f) 14 companies were sold to foreigners on the basis of Pre-emptive rights (outside the control of ZPA);

(g) 16 companies were sold to foreigners on competitive bid basis;

(h) 12 companies were disposed of through winds-up and liquidation; and

(i) 16 companies were disposed of by public flotation through ZPA ef-forts.

Clearly, the privatisation process conducted mainly through competitive bidding does not seem to have provided any room for anyone wishing to steal or corruptly obtain any assets or enterprises on offer, let alone pock-et the proceeds from the privatised assets or enterprises, since such pro-ceeds were directly collected by the Zambia Revenue Authority—which assumed the functions of the Department of Taxes and the Department of Customs and Excise from the date of its establishment on April 30, 1993 by the Zambia Revenue Authority Act No. 23 of 1993.

Also, one wonders how any individual could have been crafty enough to succeed in corruptly gaining access to any of the assets and/or enterprises under the surveillance of all the members of the ZPA’s Board of Directors and all the expert personnel from the six or so agencies sponsored by de-velopment partners!

It is also important to note that we have had the Frederick Chiluba, Levy Mwanawasa, Rupiah Banda, Michael Sata, and Edgar Lungu administra-tions since the privatisation of State assets.

Incidentally, the World Bank, cited by Fundanga and Mwaba (1997:8), rated our beloved country’s privatisation programme in 1996 as having been “the most successful” in sub-Saharan Africa, and that it offered “many examples of best practice.”

Why, then, should we start casting doubts about the probity and veracity of the people who presided over, as well as those who performed the vari-ous tasks of, a process that was highly rated by the World Bank—a highly reputable and genuine global institution—30 years later?

REASONS TO RE-PRIVATISE

In practically all affluent nations of the world today, privately owned and operated business under¬takings are the major institu¬tions that are in the forefront searching for efficient and effec¬tive ways and means for application in the creation and delivery of a cornucopia of high-quality goods and services at competitive prices.

In these nations, business entities, as Davis and Frederick (1984:454-455) have noted, are greatly depended upon to keep the stream of discover¬ies flowing in the form of consumer goods and services. This certainly calls for compet¬i¬tive business systems, which are generally and conspicu¬ously lacking in countries whose economies are based on socialist ideals and monop¬olis¬tic govern¬ment policies.

History, and what has happened to countries worldwide whose economies are, or have been, based on socialist ideals, should offer us guidance. In the following sub-sections, I have cited examples of socioeconomic ills associated with government ownership of the means of production and distribution should give us the impetus to re-privatise SOEs under IDC group of companies.

3.1 Cuba:

The country’s economy is dominated by state-run enterprises. The gov-ernment owns and operates most industries in the country. Currently, the country is currently experiencing the worst economic crisis in its history. Akin to Zambia’s unpalatable experiences during the late 1980s, stores in Cuba no longer routinely stock products including eggs, flour, chickens, cooking oil, rice, powdered milk, and ground turkey.

These basic commodities disappear from shops for days or weeks. Hours-long lines appear within minutes of trucks showing up with new supplies, and shelves are often empty the same day.

3.2 East Germany:

East Germany had a command economy—an economy captained by State enterprises. It experienced economic problems similar to those experi-enced by other socialist countries worldwide. Prior to the end of World War II in 1945, a War that started in 1939, East Germany and West Germa-ny were one country. After the War, Soviet forces occupied eastern Ger-many, while French, British and U.S. forces occupied the western half of the country.

The Berlin Wall was constructed by East Germany with the help of the now-defunct Soviet Union in 1961 to prevent the socialist country’s citi-zens from escaping to the more affluent and democratic West Germany.

At least 171 East Germans were killed trying to defect to West Germany, while more than 600 border guards and 4,400 other refugees “managed to cross the border [illegally] by jumping out of windows adjacent to the wall, climbing over … barbed wire, flying in hot air balloons, crawling through … sewers, and driving through unfortified parts of the Wall at high speeds”—History.com Editors, 2019.

The introduction of perestroika and glasnost in the former USSR by the Mikhail Gorbachev administration in 1987 and the eventual break-up of the USSR on December 26, 1991 occasioned the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, which separated communist East Germany and capitalist West Ger-many, in November 1989 and eventual reunification of the two countries into a united capitalist Germany upon the signing of a reunification treaty on August 31, 1990.

3.3 Venezuela:

Shortages of regulated food staples and basic necessities are widespread mainly following the country’s enactment of price controls and other so-cialist policies. The severity of the shortages has led to the largest refugee crisis ever recorded in the Americas. There are shortages of milk, meat, coffee, rice, oil, precooked flour, butter, toilet paper, medicines, and per-sonal hygiene products.

Hours-long lines have become common, and those who wait in them dis-appointingly go back to their homes empty-handed. Some citizens have resorted to eating wild fruit and garbage.

The country has been governed for the past 20 years by the socialist PSUV party. From 1999 to his death in 2013, Hugo Chávez was president. He was succeeded by his right-hand man, Nicolás Maduro. During its two decades in power, the PSUV has gained control of numerous key econom-ic institutions.

On September 24, 2019 in a speech delivered at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, Jair Bolsonaro, President of Brazil, uttered the following words relating to the socioeconomic ills facing Venezuela: “It is fair to say [that] socialism is working in Venezuela—they are all poor.”

3.4 Zimbabwe:

The economic history of Zimbabwe began with the transition to majority rule in 1980 and Britain’s ceremonial granting of independence. The new government under Prime Minister Robert Mugabe promoted socialism and Marxist-type rule. Within 20 years, the country has had unprecedented socioeconomic woes, rampant corruption and political instability, which have continued to haunt the country to date.

Note: In October 2001, Zimbabwean president, the late Mr. Robert Mugabe, stunned the world by abandoning his country’s economic liberalization efforts. News headlines in this regard were self-explanatory: “Mugabe Returns Zimbabwe to Socialism” (Independent Online, 2001) and “Zimbabwe a Step Closer to Marxist-Style Economy” (Independent Online, 2001).

3.5 The Soviet Union:

The Soviet economy was based on State ownership of the means of pro-duction and distribution. In May 1985, newly “elected” Mikhail Gorba-chev delivered a speech in which he publicly criticised the Soviet Union’s inefficient socialist / communist system. This was followed by a February 1986 speech to the Communist Party Congress, in which he talked about the need for political and economic restructuring—that is, Perestroika—and called for a new era of transparency and openness—that is, Glasnost.

It was reasoned that the lack of open markets which could have provided price signals and incentives to direct economic activity led to waste and economic inefficiencies. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ceased to exist on December 31, 1991.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andersson, Per-Ake, Bigsten, Arne and Persson, Håkan, “Foreign Aid, debt and Growth in Zambia,” Research Report No. 112, Nordiska Afrikainsti-tutet, Sweden, 2000.

Anglo-American PLC, “Adherence to the OECD Guidelines for Multina-tional Enterprises in Respect of Its Operations in Zambia: Submission to the UK National Contact Point Introduction,” January 2002.

Bigsten, A., Mulenga, S. and Olsson, O., “The Political Economy of Mining in Zambia,” Mimeo (World Bank: Washington DC., 2010).

Chilipamushi, D. M., “Invest¬ment Promotion and the Pri¬vatisa¬tion Process in Zambia,” in Deassis, N.A. and Yikona, S.M., editors, The Quest for an Enabling Envi¬ronment for Develop¬ment in Zambia: Se¬lected Readings (Ndola, Zam¬bia, 1994).

Chitalu, V., quoted in Kyambalesa, Henry, Quota¬tions of Zambian Origin Second Edition (Lusaka, Zambia, 1996).

Davis, Keith and Frederick, William C., Business and Society: Manage-ment, Public Policy, Ethics (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1984).

Fundanga, Caleb M. and Mwaba, Andrew, “Privatisation of Public Enter-prises in Zambia: An Evaluation of the Policies, Procedures and Experi-ences,” African Development Bank: Economic Research Papers No. 35, 1997.

Ham, M., “Luring Investment,” Africa Report, Septem¬ber/October 1992.

Independent Online, “Mugabe Returns Zimbabwe to Socialism,”

http://www.iol.co.za/, October 15, 2001.

Independent Online, “Zimbabwe a Step Closer to Marxist-Style Economy,”

http://www.iol.co.za/, October 17, 2001.

Moussa, A., quoted in Chomba, G. and Chonya, M., “New Economic Era Dawns,” Zambia Daily Mail, http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/, November 1, 2000.

Mwewa, L., quoted in Kyambalesa, Henry, Quota¬tions of Zambian Origin Second Edition (Lusaka, Zambia, 1996).

Nyakutemba, E., “Chiluba Plunges into the Market,” New African, May 1992.

Ouattara, A.D., “Africa: An Agenda for the 21st Century,” in Finance and Development, Volume 36/Num¬ber 1, March 1999.

Pitelis, C. and Clarke, T., “Introduction: The Political Economy of Priva-tisation,” in Clarke, T. and Pitelis, C., editors, The Political Economy of Privatisation (London, England, 1993).

Thole, G., “No More Parastatal Privatisation, Declares Chiluba,” Infor-mation Dispatch Online, http:///www.¬dispatch.co.zm/, January 19, 2001.

Wikipedia, “Shortages in Venezuela,”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shortages_in_Venezuela/

USAID, “Zambia,” https://www.usaid.gov/zambia/, September 24, 2020.

ZPA (Zambia Privatisation Agency) Press Release, Times of Zambia, Octo-ber 3, 1996.

Rodriguez, Andrea and Weissenstein, Michael, “Shortages Hit Cuba, Rais-ing Fears of a New Economic Crisis,” Associated Press:

https://apnews.com/article/efb7313888ca4b61824f5b293ae9cade, April 20, 2019.

McCauley, Martin and Lieven, Dominic, “The Gorbachev Era: Perestroika and Glasnost,” Britannica:

https://www.britannica.com/place/Russia/The-Gorbachev-era-perestroika-and-glasnost

BBC News, “Venezuela Crisis in 300 Words,”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-48121148/, January 6, 2020.

*The author, Henry Kyambalesa, is a retired academic. He has pursued studies in Business Administration and Management at the University of Zambia and Oklahoma City University, Mineral Economics at Colorado School of Mines, and International Studies (including the fields of Interna-tional Business, International Economics, International Relations, and In-ternational Technology Analysis and Management) at the University of Denver.

He has served as adjunct Assistant Dean and tenured lecturer in Business Administration in the School of Business at the Copperbelt University, and on the MBA Affiliate Faculty at Regis University in Denver, Colorado, USA. He has also served as Instructor in Economics, Marketing and Sta-tistics at the former Zam¬bia Institute of Technol¬ogy, and as a Guest Lec-turer in Supervi¬sion, Produc¬tion Manage¬ment and Manage¬ment Devel¬op-ment at Mindolo Ecumeni¬cal Founda¬tion in Zambia.

Privatization of Public Enterprises in Zambia: An Evaluation of the Policies, Procedures and Experiences